Concept of Garden Cities

Following the Industrial Revolution, numerous European metropolises faced an unknown rise in the rate of population growth, boosted by the migration of people from pastoral areas to civic areas seeking better openings.

Although metropolises came more inviting, problems similar to pollution and the growth of informal agreements also boosted.

Meanwhile, the country handed propinquity to nature and a cornucopia of natural coffers, but it also suffered from insulation and a drop in employment openings.

In light of these issues, in the late nineteenth century, the conception of theater metropolises was created. This model of civic planning was characterized by progressive ideals to break the problems of pastoral flight and the performing unruly growth of civic areas. The theater megacity conception was grounded on the creation of a series of small metropolises that would combine the advantages of both surroundings.

Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928), who had been studying metropolises before the establishment of urbanism as an academic field, was one of the most influential people behind the theater megacity movement. Howard published Tomorrow a Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), a book that was distributed four times latterly as Garden Metropolises of Hereafter (1902), for which he came extensively known. In addition to his publications, Howard also organized the Garden City Association in 1899 in England to promote the ideas of social justice, profitable effectiveness, beautification, health, and well-being in the terrain of municipality planning.

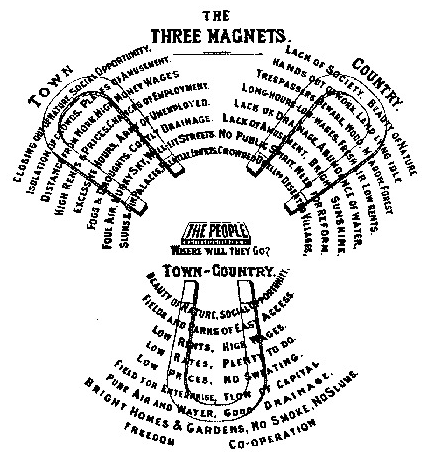

The Three Magnets Diagram, by Ebenezer Howard. Via Wikimedia Commons

The Three Attractions Diagram, particularly representational in terms of recapitulating the ideas of theater metropolises, is featured in the first runners of both performances of Garden Metropolises of Hereafter. Each illustrated attraction represents a specific terrain the city, the country, and the city- country. The first two attractions list the cons and negatives of city life and country life, while the third attraction combines the advantages of both. This third attraction contains similar promising rates of the theater megacity that it shifts the title to the center of the illustration, as opposed to the first two, suggesting a strong magnet between the question The people where will they go? And the numerous advantages offered by this model of civic planning.

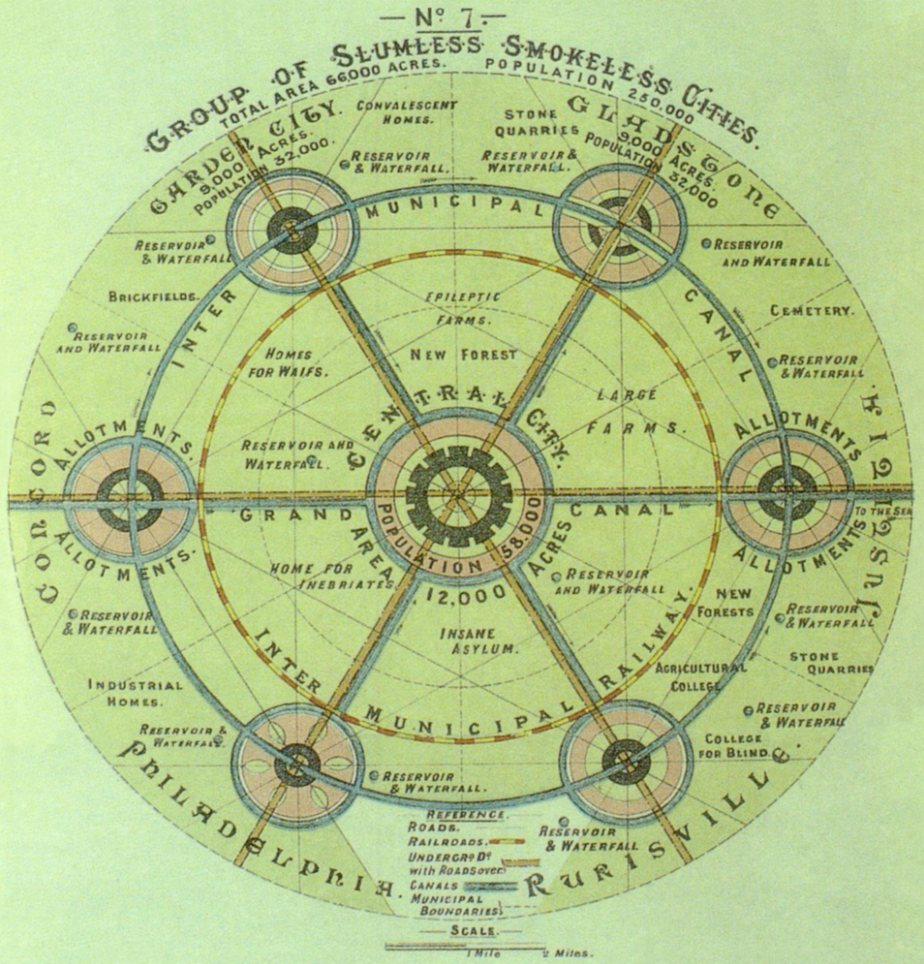

The idealized vision of the theater megacity contained specific romantic rudiments like small communities planned on a concentric pattern that would accommodate casing, assiduity, and husbandry, girdled by greenbelts that would limit their growth. Numerous plates and charts illustrate clusters of several theater metropolises, which was an important aspect to ensure the effectiveness of the theater metropolises.

Metropolises like Letchworth, Welwyn, and Stockfeld in England, were erected using these ideas, but the conception was influential in other countries too, indeed outside Europe, with acclimations and reinterpretations according to different geographical and literal surrounds.

This conception is still constantly redefined to this day-albeit vastly different from the original idea-to propose civic planning results that essay, at least in the proposition, lesser integration between civic areas and green spaces.

But indeed considering this theoretical and abstract gap between Howard’s ideas and the more recent civic planning systems, the ultimate clearly highlights the significance of studying and understanding these generalities to this day.